Ten years ago, blues guitarist Guy Davis was quietly packing up after a recording session at 90.7 WFUV at Fordham University when I approached him to ask a sensitive question.

As a student, I was working at the radio station and researching a thesis about the concept of “selling out” in popular music. I wondered why so many hip hop artists talk about selling their soul to the devil, or why bluesman Robert Johnson, one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, was said to have sold his soul to the devil at a crossroads in Mississippi in return for success.

“Selling out” can be difficult to define, yet in the arts it generally means changing the style and substance of your art to achieve commercial success. In theory, anyone can sell out, yet the concept has been said to “haunt the African American imagination” in particular.

So I decided to ask Guy Davis about Robert Johnson at the crossroads.

“I think every Black performer in this country has his or her own crossroads moment at one point in a career,” he told me. Davis also shared old expressions he had heard in the blues world which suggest there is no easy “right” or “wrong” answer to the question. “Guys would say, ‘Sure I sold out. Every night on the marquee, it said Sold Out.’”

Davis is the son of actress Ruby Dee and actor Ossie Davis, African American entertainment royalty. Both performed in canonical films about the Black American experience, and served as emcees for the 1963 March on Washington. Dee began her career with the American Negro Theatre, working with Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte. Raised in this setting, Guy Davis would have had a fundamental understanding of the unique choices Black performers face in the U.S.

In Davis’s metaphor, the crossroads represents one of those choices: a negotiation, a balance, even a “moral dilemma” in the words of author Katrina Dyonne Thompson in Ring Shout, Wheel About: The Racial Politics of Music and Dance in North American Slavery.

What is really at stake at the crossroads I may never completely understand, because I am not Black. Still, I was easily able to see the spectre of the sellout lurking beneath the surface of the Super Bowl Halftime Show earlier this month.

Symbolism or Substance?

Kendrick Lamar, one of the great Black performers of his generation, earned the largest audience ever for a Halftime Show, 133.5 million people, even larger than the game itself.

The crescendo and centerpiece of the performance was Kendrick’s 2024 Grammy-winning Song of the Year “Not Like Us.” The record criticizes Drake for pedophilia and sexual misconduct, yet the more meaningful criticism may come when Kendrick labels Drake a “colonizer,” or a sellout, in the final verse. By referencing slavery and the Old South in this verse, the song links the concept of selling out in music to older ideas about betrayal in African American culture.

One old conception of betrayal in African American culture is “Uncle Tom.” Born from the 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the slur is used to disparage a Black person who is perceived as subservient or deferential to white people. Actor Samuel L. Jackson portrayed Uncle Sam during the halftime performance, but he also famously portrayed a villainous Uncle Tom in the 2012 film “Django Unchained.” People have pointed this out including Blacks of Are.na, who called Jackson’s Super Bowl casting “intentional” for this reason.

“Not Like Us” and the Uncle Sam Uncle Tom entendre can be seen as subtle references to the negotiation Black performers in the United States are subject to.

The mainstream liberal press showered attention and adulation on the symbolism in Kendrick’s performance. Some writers suggested Kendrick Lamar was dissing President Donald Trump, who was in attendance. The New York Times wrote, “This was more than just a rap performance; it was a critique of American culture on what many consider an unofficial holiday in America, Super Bowl Sunday.”

Yet other writers were left wanting more from the performance, like Natalie Collier from Jackson Mississippi, Founder of The Lighthouse / Black Girl Projects:

I’ll grant it that Samuel L. Jackson’s Uncle Sam narrating character was interesting….Even Serena Williams c-walking to a diss track about her ex, cute but … <shrugs shoulders> It wasn’t radical; at best, it was innocuous. There will be people who respond to my propositions with things like “You just don’t get it.” But I did. “What more do you want him to do?” A lot.

Discordia Review suggests the symbolism was just that: symbolic. “Any criticism of America in the performance was kept firmly within the realm of the plausibly deniable.” They also point out Kendrick was performing for the NFL, an organization that famously cracks down on anti-racist activism. The week before the Super Bowl, the NFL decided to remove the phrase “End Racism” from the field to conform to President Trump’s war against diversity.

Many journalists and fans have long believed Kendrick Lamar to be a paragon of activism in music, even “hip-hop’s conscience.” Yet by performing at the Super Bowl, and choosing not to directly speak any truth to power, could Kendrick be guilty of the same sort of betrayal, or “selling out,” that he criticizes?1

Jumping Jim Crow

Any debate about the presence of political speech in popular music must consider the history of cultural production, and the history of hip-hop music in particular.

During the 1990s and 2000s, as just four firms came to dominate the music industry, grassroots messages in the tradition of early hip-hop and rap became less and less common on the Billboard Magazine’s Hot 100 chart. This mirrors early 20th century theories that suggest cultural industries (music, movies, etc.) produce culture as a commodity, and therefore industry gatekeepers may not sponsor forms of culture that are seen as less marketable. In other words, corporate ownership can impact cultural content, and commercial pressures can limit the circulation of certain ideas perceived as either unmarketable or simply undesirable to the corporate music power structure.

This is a technical, theoretical way to describe the crossroads in Guy Davis’s metaphor. Artists face a negotiation between commercial success and free expression. For Black performers, the negotiation is more complicated because of the racial history of music and dance in the United States, and because “free expression” has often taken the form of cries against oppression, and critiques of the dominant society.

After arriving in the Americas as captives, Africans used music and dance to subvert white rule and express their true selves, while the dominant white culture used music and dance to control and demean the Africans.

“Performing arts allowed West Africans to preserve their distinct cultures and enabled them to conceal rebellions, retain homeland traditions, and encourage their spirits,” Katrina Dyonne Thompson writes in Ring Shout, Wheel About. Meanwhile, white authorities constantly forced African Americans to perform, like when slave drivers forced slave coffles to sing and “act lively” when entering town, so the enslaved people would be perceived as energetic and sell for a higher price.

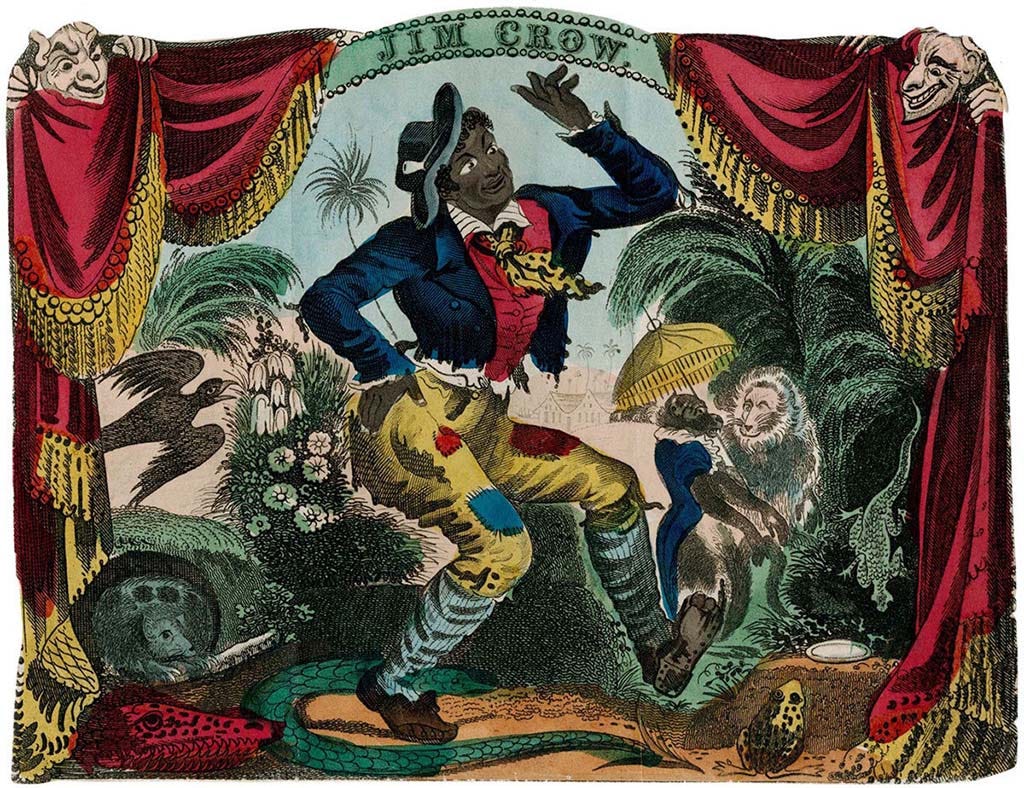

During this era, many white men became famous by painting their faces black and mimicking these forced forms of African American expression in what came to be called “blackface minstrelsy.” The most famous was probably Thomas Dartmouth Rice, who during the 1830s created the character Jim Crow, a rheumatic Black man who would sing and dance. Jim Crow became one of the best known and most-loved theatrical personalities of the 1800s in the United States as well as Great Britain.

Wheel about, and turn about, and do just so

Every time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow

So while the dominant society suppressed and manipulated African Americans’ own free expression, blackface minstrelsy, a distorted version of Black music and dance, became extremely popular. As a result, African Americans found it challenging to perform music and dance on their own terms.

For example, after the African Grove Theater in New York City closed in 1823, Black Shakespearean actors James Hewlett and Ira Aldrige struggled to find work elsewhere, as audiences seemed to prefer blackface stereotypes to actual Black performers. “In order for black entertainers to succeed in their industry,” Dyonne Thompson writes, “they needed to impersonate the white mimicry of the facade of bondsmen and bondswomen performing music, song, and dance choreographed by whites.”

All of this demonstrates how commercial pressure and racism have always made it challenging for African American performers to share authentic representations of themselves in popular music and culture. African American performers have had to reclaim their identity from the dominant culture, while at the same time performing for the dominant culture.2 This begins to illustrate what is really at stake at the crossroads.

Soul Doubt?

Kendrick Lamar’s lyrics demonstrate that he has always been hyper-aware of the discourse around selling out. His 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly, widely considered his magnum opus, includes a narrative about negotiating your identity in an industry which seeks to “pimp” and control you. For example, in the skit “For Sale,” a character named “Lucy,” or Lucifer, the devil, presents the artist with a contract. Kendrick addresses selling out more recently and more explicitly on his latest album GNX when he says in “Wacc’d Out Murals,” “I never lost who I am for a rap image.”

In this context, by drawing attention to the concept of the sellout during the Super Bowl, Kendrick could be offering a subtle and self-aware commentary on the limitations of his own project. While he is socially conscious, he can perform on the biggest stage in the country because he is commercially successful. And since socially conscious content can jeopardize commercial success, someone in Kendrick’s position has to tread lightly. He must operate in the realm of symbolism because more overt political speech could sink the project. This is the game, or the “American Game,” as Samuel L. Jackson put it during the performance.

Yet where is the line? What truly separates working against the system, working within the system, and working for the system? These questions are vexing, and as Guy Davis intimated, the “right” and “wrong” answers are illusive for African American entertainers, and grasped only vaguely by the rest of us Americans.

What’s the best way to play the game? Can someone truly know if they do not play?

This debate resembles a historical split in the field of critical race theory, the study of the relationships between race, racism, and power. When the field began, it was split into two camps. “Idealists” believe racism and discrimination are ways of thinking, and we should focus on changing the images, attitudes, and social teachings around race. In other words, symbols matter. “Realists” consider racism to be a means by which society allocates resources and status, and we should focus on changing material conditions and delivering tangible benefits to marginalized groups. In other words, results matter. Does the symbolism and representation matter? Or is it a poor substitute to changes in material conditions? Are these two camps mutually exclusive? For more see “Critical Race Theory: An Introduction” by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, New York University Press, 2017.

This could be a manifestation of what W.E.B. Du Bois called “double consciousness,” or the struggle African Americans face to remain true to Black culture while at the same time conforming to the dominant white society.

Love the historical approach on the analysis, and as he said it himself, "I wanna perform their favorite song" so the people's choice played into it too!

When it’s all said, the performance was more about entertainment than social criticism